Windows debugging for fun and profit

I had an old friend visiting over the holidays. When he asked me for some help regarding assembly, I knew I’d be in for some fun.

He likes to play Japanese visual novels and other games as a way to learn Japanese. However, typing kana can be difficult, since that requires knowing how to read the kana. For the hiragana and katakana syllabaries, it’s not so bad since they’re only about 40 characters a piece. For kanji on the other hand, knowing the correct readings can take a lot of study time.

Since these are games, you can’t just copy and paste the text into a dictionary; the text is drawn on the window. However, at some point, before being rendered, the text does exist as text in the program memory. Inserting a hook into the drawing routine for text would be enough to extract those characters and display them in another window, or write them to the clipboard.

There are already some general-purpose tools to do this, such as Anime Games

Text Hooker (AGTH), which can be used to hook the text of many games using

so-called H-codes. An H-code specifies a hook location and some rudimentary

code for how to interpret the processor state at the hook location in order to

extract the character. For example, an H-code could specify that the breakpoint

is at address 0x008A0275 and that the character is in register eax.

If only it were that simple. In lots of Japanese software, especially games,

text is encoded not in ASCII, nor in Unicode, but in Shift-JIS (SJIS). Some

SJIS characters are coded on one byte, and some are coded on two bytes, with

the distinguishing characteristic between the two being the value of the first

byte: if the first byte is less that 0x80, then the character is coded on one

byte; else, the character is coded on two bytes.

Accordingly, H-codes are somewhat more complicated, as the breakpoint given in an H-code might only have one half of a character.

All that to say that I couldn’t manage to write an H-code for this game that my friend was interested in.

But instead of giving up, I decided instead that I could just write a little debugger of my own, that would insert a breakpoint at the right place in the game’s code, inspect the processor state to find the text address, and read the game’s memory to extract the text.

It can’t be that hard can it ?

Exploring the game’s code

First we need to find out where the game’s code reads the text, so that we can insert our hook there.

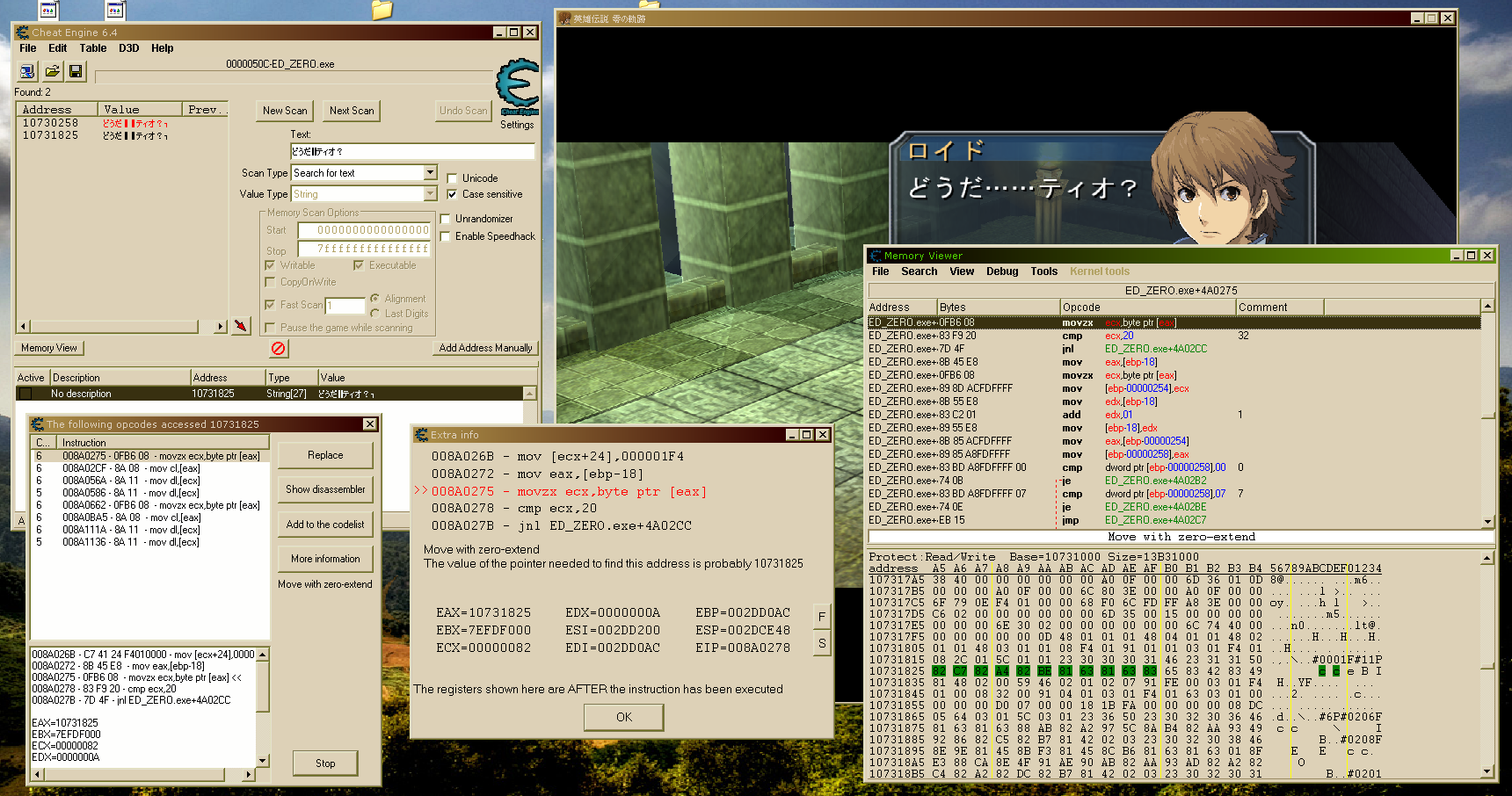

Let’s fire up the game and hook it with Cheat Engine. The only hint I have to go on from my friend is the first string that a character says in game.

どうだ……ティオ?

Let’s search for the string shortly before it gets displayed. The rationale for doing this is that we’ll find an address pointing to some kind of text or event script database rather than some kind of transient memory. Since we want to find the code that reads from this address, let’s put a read watchpoint on the address, and then wait for the text to get displayed. Here’s what that all looks like on screen after the watchpoint gets hit.

Note that the string that we searched for is highlighted in the memory view window since we have watchpoints on those addresses.

It looks like the address gets read several times in fact! Since all these instructions run about the same number of times, I suppose it doesn’t really matter which one we pick to use for our hook, so let’s just arbitrarily pick the first one.

In the extra info window, we can see that the address of the string that we

found is held in the eax register. This looks like it’s where we would want

to put our hook, but frankly, I’m not convinced yet.

To start with a clean slate, let’s restart the game. Then let’s put a breakpoint on the instruction to see what triggers it and to inspect the processor state when the instruction executes.

Each time the instruction executes, the value of eax seems to be increasing.

To me, this suggests that it’s reading the text character by character. That

also explains why our watchpoint was triggered several times: our watchpoint

was spread out over the string we searched for and characters are being read

one by one. Let’s follow eax and see how the text is being

read.

23 30 30 30 31 46 23 31 31 50 82 C7 82 A4 82 BE 81 63 81 63 83 65 83 42 83 49 81 48 02 00

^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^ ^^The top row shows successive bytes of memory of memory starting at the address

pointed to by eax the first time the breakpoint hit up to the address pointed

to by eax after which continuing the execution of the program returned

execution completely to the game, breaking execution out of the loop it seemed

to be in.

The bottom row shows precisely which byte eax was pointing at when the

breakpoint hit. The breaks all occurred from left to right.

Now, 82 C7 82 A4 82 BE 81 63 81 63 83 65 83 42 83 49 81 48 is simply the

Shift-JIS encoding of どうだ……ティオ?. But what’s the rest? The 00 at the

end is surely just a null terminator. The 02 is probably also some kind of

end-of-message signal.

What about the beginning though? Let’s look at it in ASCII.

23 30 30 30 31 46 23 31 31 50

# 0 0 0 1 F # 1 1 PNo idea what that means, but it’s probably some kind of metadata since it doesn’t appear explicitly in the displayed text.

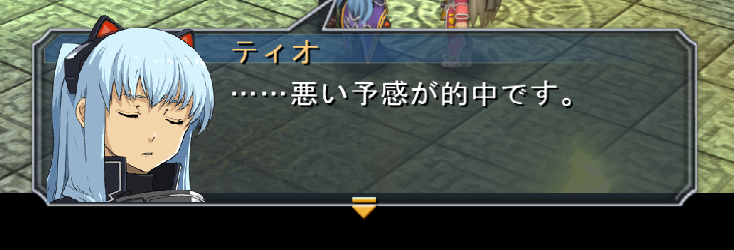

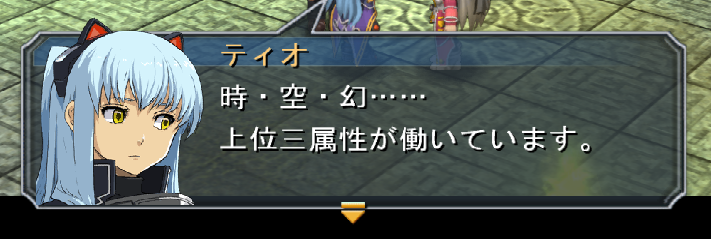

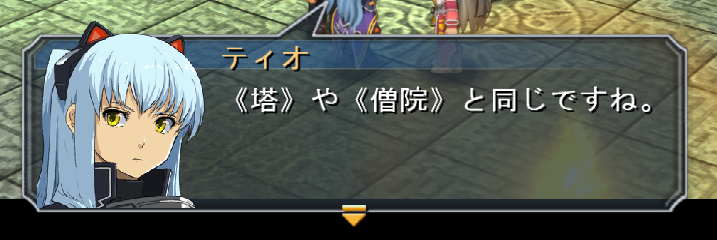

Let’s look at the text-script for the next message, which is longer and more complicated.

23 36 50 23 30 32 30 36 46

# 6 P # 0 2 0 6 F

81 63 81 63 88 AB 82 A2 97 5C 8A B4 82 AA 93 49 92 86 82 C5 82 B7 81 42

… … 悪 い 予 感 が 的 中 で す 。

02 03

?? ??

23 30 32 30 38 46

# 0 2 0 8 F

8E 9E 81 45 8B F3 81 45 8C B6 81 63 81 63

時 ・ 空 ・ 幻 … …

01

??

8F E3 88 CA 8E 4F 91 AE 90 AB 82 AA 93 AD 82 A2 82 C4 82 A2 82 DC 82 B7 81 42

上 位 三 属 性 が 働 い て い ま す 。

02 03

?? ??

23 30 32 30 31 46

# 0 2 0 1 F

81 73 93 83 81 74 82 E2 81 73 91 6D 89 40 81 74 82 C6 93 AF 82 B6 82 C5 82 B7 82 CB 81 42

《 塔 》 や 《 僧 院 》 と 同 じ で す ね 。

02 00

?? endAnd this is the result of this text-script in-game.

Comparing the result with the script, it looks like #XXXXF identifies the

speaker’s face, the 02 marker acts as end-of-panel, 01 acts as a line

break, and 03 acts as next-panel.

Comparing for a few more messages like this suggests that #XXP identifies

which character is speaking.

So this instruction movzx ecx, byte ptr [eax] at address 0x008A0275 is

precisely where we want to put our hook. Each time the breakpoint hits, we have

a sort of cursor in memory given by eax, and depending on the value under the

cursor, we can figure out when panels break, when lines end, who’s speaking,

etc.

It’s everything we could ever want in a text hook and more !

Building the debugger

Setting the breakpoint

Debugging a program is a very event-driven process. The debugger responds to

different events that occur in the program such as the program starting and

ending, loading and releasing DLLs, creating and destroying threads, and

throwing exceptions. The latter kind of event is the one that interests us the

most because breakpoints are implemented as exceptions. In fact, a breakpoint

is nothing more than a special kind of instruction, int 3, affectionately

called “trap to debugger”, that when handled by Windows will cause the running

program to throw a special kind of debug exception which can then be handled by

a debugger.

The interrupt instruction is coded on two bytes, with the first distinguishing

it from other types of two-byte opcodes and the second being an arbitrary

one-byte value to use as the interrupt number. However, the trap to debugger

interrupt is so useful that it has its own dedicated one-byte opcode 0xCC.

All that’s great, but it means that the int 3 instruction needs to be in the

program code to begin with so that we can debug it. That’s a

specifically opt-in debugging strategy. In order to insert a breakpoint into

a program without it necessarily asking for it, we need to overwrite (part of)

the instruction we want to break on with 0xCC. That destroys the original

instruction though, so we have to find some way to nonetheless execute the

original instruction. We’ll get to that later though.

In Windows, we can change the memory of a running process with the

WriteProcessMemory function. However, we don’t want to change regular data.

We want to change the program code, which is in the .text segment of the

process memory, and the .text segment is read-only. Well, “read-only” is

really just a nebulous sort of hocus pocus concept anyway. To change the

protection of memory regions in another process, it suffices to use the

VirtualProtectEx function, which according to the documentation “changes the

protection on a region of committed pages in the virtual address space of a

specified process.” That’s just fancy OS jargon for “make read only memory

writable” or “make data memory executable” in another process.

However, it would be pretty ridiculous if any old process could just write to

the memory of another process or its memory protection. WriteProcessMemory

requires the PROCESS_VM_WRITE and PROCESS_VM_OPERATION permissions and

VirtualProtectEx requires just the PROCESS_VM_OPERATION permission. Also,

these two functions require a HANDLE on the target process.

There are two strategies for acquiring a handle on a process and getting the necessary privileges.

- Using the

CreateProcessfunction and passing theDEBUG_ONLY_THIS_PROCESSflag. This confers all privileges on the child process to the parent process, andCreateProcessconveniently returns a handle to the child. - Using the

OpenProcessfunction passing in the process ID and the bitwise OR of the desired privileges. This can only be done if the process wanting to acquire the handle has theSeDebugPrivilegeprivilege in its access token.

In the former case, our text hooking program would be taking care of spawing the game. In the latter case, our software would be hooking into the game after the game has started.

The first option sounds simpler than the second option, but when I tried it,

CreateProcess would always fail with rather obscure error codes. On the other

hand, I’ve successfully managed to use the second strategy in the past, so I

figured I might as well give it a go again. Also, I personally find the second

strategy more elegant in the sense that the concerns of the software are better

separated.

Processes sadly don’t just start with the SeDebugPrivilege privilege in their

access token, so we need to modify our program’s access token using the

AdjustTokenPrivileges function after getting a handle on our access token

using the OpenProcessToken function passing in the TOKEN_ADJUST_PRIVILEGES

and TOKEN_QUERY flags.

After acquiring the SeDebugPrivilege privilege, we need to get the process ID

of the game so that we can use OpenProcess and finally call

VirtualProtectEx and WriteProcessMemory. We can list all running processes

and compare their executable’s name with the name of the game’s executable

(which is rather distinctive, so it’s unlikely that we’ll accidentally get

something else) using the functions CreateToolhelp32Snapshot,

Process32First and Process32Next.

The first of those three creates a snapshot of the running processes. The

Process32First and Process32Next functions allow us to walk over the

snapshot, getting a PROCESSENTRY32 struct for each of them. This struct has

two important fields.

szExeFileholds the name of the executable that spawned the process.th32ProcessIDholds the process ID that we can use withOpenProcess.

All that being said, here’s the code for setting the breakpoint.

First, we have to escalate the privileges of our process so that it can call

OpenProcess.

HANDLE token;

// ^ our process's access token

LUID debug_luid;

// ^ the locally-unique identifier for the SeDebugPrivilege privilege

// Look up the SeDebugPrivilege privilege's LUID.

if(!LookupPrivilegeValue(NULL, SE_DEBUG_NAME, &debug_luid))

{

printf("Failed to look up debug privilege name. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// Open our process's access token with the necessary privileges to modify it.

if(!OpenProcessToken(GetCurrentProcess(), TOKEN_ADJUST_PRIVILEGES | TOKEN_QUERY, &token))

{

printf("Failed to open process access token. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// The TOKEN_PRIVILEGES structure expected by AdjustTokenPrivileges uses the

// so-called 'struct hack' to have dynamic size, so we have to allocate enough

// memory for the structure itself plus one item for the contents of the

// dynamic array at the end.

PTOKEN_PRIVILEGES tp

= (PTOKEN_PRIVILEGES)malloc(sizeof(*tp) + sizeof(LUID_AND_ATTRIBUTES));

tp->PrivilegeCount = 1;

tp->Privileges[0].Luid = debug_luid;

tp->Privileges[0].Attributes = SE_PRIVILEGE_ENABLED;

// Adjust the privileges in our token.

if(!AdjustTokenPrivileges(token, FALSE, tp, sizeof(*tp), NULL, NULL))

{

printf("Failed to adjust token privileges. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// Clean up

CloseHandle(token);

free(tp);Next, we have to enumerate the running processes to find the process ID of the game.

HANDLE process_snapshot;

// ^ A handle to the snapshot of the currently running processes

PROCESSENTRY32 pe;

// ^ A single process entry, used as the traverse the snapshot.

char found;

// ^ A boolean for whether we found the game or not.

// Create the snapshot of the currently running processes.

if(INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE ==

(process_snapshot = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot(TH32CS_SNAPPROCESS, 0)))

{

printf("Failed to get process list. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// Before using Process32First, we need to initialize the size of the

// destination structure, for some reason.

pe.dwSize = sizeof(pe);

// Get the first process entry.

if(!Process32First(process_snapshot, &pe))

{

printf("Failed to get process from list. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// And start the loop to traverse the snapshot.

found = 0;

do

{

// Compare the name of the process's executable with the expected name of

// the game's executable.

if(wcscmp(pe.szExeFile, GAME_PATH) == 0)

{

found = 1;

break;

}

}

while(Process32Next(process_snapshot, &pe));

if(!found)

{

printf("Failed to find ED_ZERO.exe; is the game running?\n");

exit(1);

}

// Get the handle on the game's process with all privileges.

// This includes the necessary PROCESS_VM_WRITE and PROCESS_VM_OPERATION

// privileges.

if(NULL ==

(game_process = OpenProcess(PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, pe.th32ProcessID)))

{

printf("Failed to open ED_ZERO.exe process. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// Attach ourselves as a debugger to the process.

if(!DebugActiveProcess(pe.th32ProcessID))

{

printf("Failed to debug ED_ZERO.exe process.\n");

}Finally, we can set the breakpoint in the process memory.

SIZE_T b;

// ^ Used as an out parameter for the number of bytes written to the process

// memory.

DWORD newprot = PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE;

// ^ The protection that we want to set on the code so that we can write to it.

DWORD oldprot;

// ^ Used as an out parameter for the old memory protection value.

const unsigned char int3 = 0xCC;

// ^ The `int 3` instruction opcode.

// Set the memory protection to our new value.

// `instruction_address` is the address of the instruction that we want to

// modify. We only want to change one byte, so we set the length of memory to

// change to `1`.

if(!VirtualProtectEx(game_process, instruction_address, 1, newprot, &oldprot))

{

printf("Failed to weaken memory protection. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// Write the opcode to the instruction we want to break on.

if(!WriteProcessMemory(game_process, instruction_address, &int3, 1, &b))

{

printf("Failed to set breakpoint.\n");

exit(1);

}

// Restore the old memory protection to avoid possibly upsetting the game.

if(!VirtualProtectEx(game_process, instruction_address, 1, oldprot, &newprot))

{

printf("Failed to reset memory protection. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}And now the breakpoint is set!

Writing the debugger loop

Like I said earlier, debugging is an event-driven process. Now we need to write the event loop that will handle debugging events, in particular exceptions, so that we can actually do the text extraction.

The key function is WaitForDebugEvent. This function will block execution of

the debugger until a debug event is received, and write it to an out parameter.

We can then dispatch to a specialized event handler according to the type of

event. In our case, we dispatch to a handler for debug exceptions (created by

the int 3 instruction we wrote into the code) and ignore all other events.

When we’re done processing the event, we call ContinueDebugEvent. Until we

call ContinueDebugEvent, the thread that triggered the event will be

suspended.

void debug_loop()

{

DEBUG_EVENT event;

ZeroMemory(&event, sizeof(event));

for(;;)

{

// Block until we receive a debug event.

if(!WaitForDebugEvent(&event, INFINITE))

{

printf("Failed to get next debug event. (Error %d.)", GetLastError());

exit(1);

}

// This function will analyze the event type and call an appropriate

// handler.

dispatch_event_handler(&event);

// Return control to the game.

ContinueDebugEvent(event.dwProcessId, event.dwThreadId, DBG_CONTINUE);

}

}Now to write the dispatch_event_handler function that’s invoked by the above

code. There are some nasty details involved here. It turns out that the first

time you hook into a process on windows, it artificially generates a breakpoint

exception to indicate (approximately) where the program entry point is. We

don’t care about the program entry point though, so we need some logic to skip

over this event to avoid handling it.

Up until now, we’ve been ignoring threads, but that won’t do anymore. Our

hooker needs to read the processor state right at the moment that the

breakpoint is hit. Processor state is thread-local, so we need to get a handle

on the thread that hit the breakpoint. To do that, we use the OpenThread

function passing in the thread ID. Thankfully, the debug event structure

contraints the thread ID, so this is easy. However, rather than call

OpenThread every time we handle the breakpoint exception, we’ll only do it

the first time for efficiency, and store the thread handle in a global

variable.

void dispatch_event_handler(LPDEBUG_EVENT event)

{

// We need to skip the first breakpoint event, since it's artificially

// generated.

static char first_try = 1;

switch(event->dwDebugEventCode)

{

case EXCEPTION_DEBUG_EVENT:

// We only bother with the exception events

switch(event->u.Exception.ExceptionRecord.ExceptionCode)

{

case EXCEPTION_BREAKPOINT:

if(first_try)

{

first_try = 0;

break;

}

// Open the game thread the second time a breakpoint gets hit.

if(game_thread == NULL)

{

if(NULL ==

(game_thread =

OpenThread(THREAD_ALL_ACCESS, FALSE, event->dwThreadId)))

{

printf("Failed to open game thread.\n");

exit(1);

}

}

// invoke the breakpoint handling routine.

on_breakpoint(game_process, game_thread);

break;

default:

printf("Unhandled exception occurred.\n");

break;

}

break;

default:

//printf("Unhandled debug event occurred.\n");

break;

}

}Finally, we can write the on_breakpoint function that will inspect the

processor state in the game thread to read the value in eax, and read the

game’s memory at that address in order to extract text or metadata. By analogy

with WriteProcessMemory, there’s ReadProcessMemory which does exactly what

we would expect. Thanks to all that debug privilege stuff we did earlier, we

have no special setup needed to use this function now.

There’s one more detail that we need to worry about though: the breakpoint that we set in the game code is overwriting an instruction that used to be doing something useful! There are at least two options available to us.

- We can remove the breakpoint, restoring the original instruction, before returning control to the game. We put the breakpoint back right after returning control to the game however.

- We simulate the instruction in the debugger.

I feel like real debuggers use a different strategy than either one of these, but I found it pretty hard to do research on this short of reading the source code of existing debuggers, which I wasn’t prepared to do for what’s supposed to be just a quick hack.

The former option seems like it introduces race conditions; we might miss a character or two before the breakpoint is restored. That leaves us only with the second option of simulating the instruction.

Thankfully, that’s not so hard. The instruction that we overwrote, movzx ecx, byte ptr [eax], copies one byte from the address pointed to by eax into

the lowest byte of ecx, filling the higher bytes with zero. Our text hooking

logic is going to need to read the value pointed to by eax anyway in order to

extract the text, so all we really need to do is do a little write to ecx,

and the game won’t be able to tell the difference.

There’s one more detail that we need to watch out for. The instruction that we

overwrote and that we’re now going to be emulating is coded on three bytes,

whereas the breakpoint that we inserted is coded on one byte. Consequently,

there are now two bytes of garbage in the program text that we need to jump

over in order to properly resume execution. To do this jump, it suffices to

increase the value of eip by two, which we can do at the same time as we

perform the write to ecx.

We can read and write the processor state of a thread with the

GetThreadContext and SetThreadContext functions, which deal in CONTEXT

structs. The contents of this struct varies from architecture to achitecture,

but on x86 it has the fields Eax, Ebx, Ecx, etc. corresponding to the

registers with the same names. The tricky thing is that the registers are

organized into groups, and when we use GetThreadContext or

SetThreadContext, we need to specify which register groups we’re reading or

writing by using the ContextFlags field of the CONTEXT struct. Since we’ll

be reading eax and writing to ecx, which are in the integer register group,

we need to use the CONTEXT_INTEGER flag. Since we also want to read and write

to eip, which is in the control register group, we’ll have to use the

CONTEXT_CONTROL flag.

Talk is cheap. Let’s see the code.

void on_breakpoint(HANDLE game_process, HANDLE game_thread)

{

char sjis[RPM_BUF_SIZE];

// ^ a buffer to hold the memory that we read from the game memory at

// the address given in eax.

SIZE_T b;

// ^ to be used as an out parameter for reading and writing memory.

CONTEXT context;

// ^ the structure holding the processor state.

LPVOID sjis_addr;

// ^ we'll store the contents of eax in here

LPVOID bp_addr;

// ^ we'll hold the current value of eip in here

// First, we read the processor state in the game thread.

// We want to read the integer registers (esp. EAX) and the control

// registers (esp. EIP)

context.ContextFlags = CONTEXT_INTEGER | CONTEXT_CONTROL;

if(!GetThreadContext(game_thread, &context))

{

printf("Failed to get thread context.\n");

return;

}

// Pull out the breakpoint address from eip and the value of eax, which

// is a pointer of the next chunk of data to be parsed.

bp_addr = (LPVOID)context.Eip;

sjis_addr = (LPVOID)context.Eax;

// As a sanity check, we'll verify that eip is right after our

// breakpoint. If it's not, then we'll bail out because it means that

// some other breakpoint that we didn't put there was hit.

// Please forgive the nasty casts.

if(bp_addr != (LPVOID)((DWORD)instruction_address + 1))

{

printf("Breakpoint hit at another address, namely 0x%08x.\n", bp_addr);

return;

}

// Now we read the memory of the game at the address that we found in

// eax in order to get the next character to be read.

if(!ReadProcessMemory(game_process, sjis_addr, sjis, RPM_BUF_SIZE, &b))

{

printf("Failed to read SJIS character from game memory @ 0x%08x. "

"Read %d bytes. (Error %d.)\n",

sjis_addr,

b,

GetLastError());

}

// The instruction that we overwrote was `movzx ecx, byte ptr [eax]`,

// which is coded on 3 bytes, so we need to jump over the next two

// bytes which are garbage.

context.Eip += 2;

// Reset the context flags to write out in case the call to

// GetThreadContext changed the flags on us for some reason.

context.ContextFlags = CONTEXT_CONTROL | CONTEXT_INTEGER;

// Simulate the overwritten instruction by moving the lowest read byte

// into ECX. We have to take care to cast it to an unsigned char to

// ensure that the value is positive, so that when the unsigned char

// gets implicitly widened to a DWORD (the type of the Ecx field), we

// actually get zeroes in the high bits instead of ones. (Tracking down

// that bug was in fact a nightmare.)

context.Ecx = (unsigned char)sjis[0];

// Flush the context out to the processor registers.

if(!SetThreadContext(game_thread, &context))

{

printf("Failed to write processor state.");

return;

}

// parse the buffer of data that we read.

parse_buf(sjis);

}The parse_buf function is pretty uninteresting, so I won’t include it here.

In a nutshell, it appends text data to a large internal buffer and skips over

metadata. It can decide whether the buffer contains metadata or text by looking

at the first byte. (Recall that the metadata always started with #.) If the

buffer starts with a null byte, then we’ve reached the end of text, and we need

to flush the large internal buffer.

But where do we flush it to?

The Windows clipboard

My friend is using a nice piece of software called Translation Aggregator, that monitors the clipboard for changes: when the contents of the clipboard changes, it updates the contents of a textbox in a window to contain whatever is in the clipboard. This textbox has some cool features, the most important of which being that hovering on a kanji will give its reading and hovering on a word will give its definition. Other text hooking software also writes to the clipboard, so this is how the usual tools all fit together.

In order to write to the clipboard, we first have to own it. To get ownership

of the clipboard, we use the OpenClipboard function. Normally, it’s not a

process but a window that owns the clipboard; that’s why OpenClipboard

takes as a parameter a handle to a window. Since our program is a simple

console application, we’ll just use NULL. (One thing I love/hate about the

Windows API is how frequently you can just use NULL for things. I think

CreateProcess takes something like 11 parameters, more than half of which can

just be NULL.)

Then, we can clear the clipboard with EmptyClipboard and finally write data

to it with SetClipboardData. The catch with SetClipboardData is that you

can’t just give it a pointer to some data in our program such as our message

buffer, because that pointer wouldn’t make sense outside our program’s address

space. The solution is to allocate globally shared memory with GlobalAlloc.

Once we pass the pointer to SetClipboardData, the Windows clipboard wants to

become the owner of the data, so when we allocate the memory with

GlobalAlloc, we need to use the GMEM_MOVABLE flag to indicate that another

process can assume ownership of the memory. Also, the fact that the clipboard

takes over ownership of the memory means that we don’t need to free it in our

code.

The Windows clipboard is a modern, sophisticated thing. It can hold all sorts

of different data. To specify what type of data we’re writing to the clipboard

we need to pass a flag to SetClipboardData. Well, we’re writing text, so we

use the CF_TEXT flag.

Alright, program finished. We fire up the game, hook our program in, and launch Translation Aggregator. But the text comes out all garbled. Well, that’s because the clipboard doesn’t know the locale/charset that the text is in!

It just so happens that there’s a field in the modern, sophisticated thing that

is the Windows clipboard that serves as a specifier for the locale. Just

passing in DWORD to specify the locale would make too much sense; you have to

pass in a pointer to the locale. Of course, just as with the text, we can’t

just use any old pointer; we have to use global memory pointers. So we

call SetClipboardData again, this time with the CF_LOCALE flag and a

global pointer to a DWORD holding the locale identifier for Japanese. Phew !

Finally we’re done with the clipboard and we can close it with

CloseClipboard.

Here’s the code.

void flush_message_buffer()

{

// msg_offset specifies how much of the internal buffer we've written

// to so far.

if(msg_offset == 0)

return; // nothing to do !

// null-terminate the buffer

msg_buf[msg_offset] = '\0';

// allocate a global buffer to give to the system with the clipboard

// data.

HGLOBAL clip_buf = GlobalAlloc(GMEM_MOVEABLE, msg_offset + 1);

// copy the message buffer into the global buffer

memcpy(GlobalLock(clip_buf), msg_buf, msg_offset + 1);

GlobalUnlock(clip_buf);

// allocate global memory to hold the locale identifier.

HGLOBAL locale_ptr = GlobalAlloc(GMEM_MOVEABLE, sizeof(DWORD));

DWORD japanese = 1041;

memcpy(GlobalLock(locale_ptr), &japanese, sizeof(japanese));

GlobalUnlock(locale_ptr);

// Open the clipboard so we can write to it.

if(!OpenClipboard(NULL))

{

printf("Failed to open clipboard. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

goto cleanup;

}

// Remove any data that might already be in the clipboard.

if(!EmptyClipboard())

{

printf("Failed to empty clipboard. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

goto cleanup;

}

// Write the text data to the clipboard.

if(!SetClipboardData(CF_TEXT, clip_buf))

{

printf("Failed to set clipboard data. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

goto cleanup;

}

// Write the locale information to the clipboard.

if(!SetClipboardData(CF_LOCALE, locale_ptr))

{

printf("Failed to set clipboard locale. (Error %d.)\n", GetLastError());

goto cleanup;

}

cleanup:

// Clear the message buffer

ZeroMemory(msg_buf, msg_offset);

// Close the clipboard

CloseClipboard();

// Reset the offset within the internal buffer to the beginning.

msg_offset = 0;

}Conclusion

All in all, I wound up using the Windows API a lot more than I ever would have liked. It’s messy. It has a lot of typedefs in uppercase. It uses TitleCase for everything. I had to code in Visual Studio. Ew.

But the text hooker works! And here’s where the “and profit” part of the title is relevant: my friend was so pleased that it worked (he had searched for hours online for H-codes and guides) that he gave me 50$.

Now let’s hope I don’t have to use my Windows XP virtual machine again for a long, long time.